… from Ajaccio to the Empire

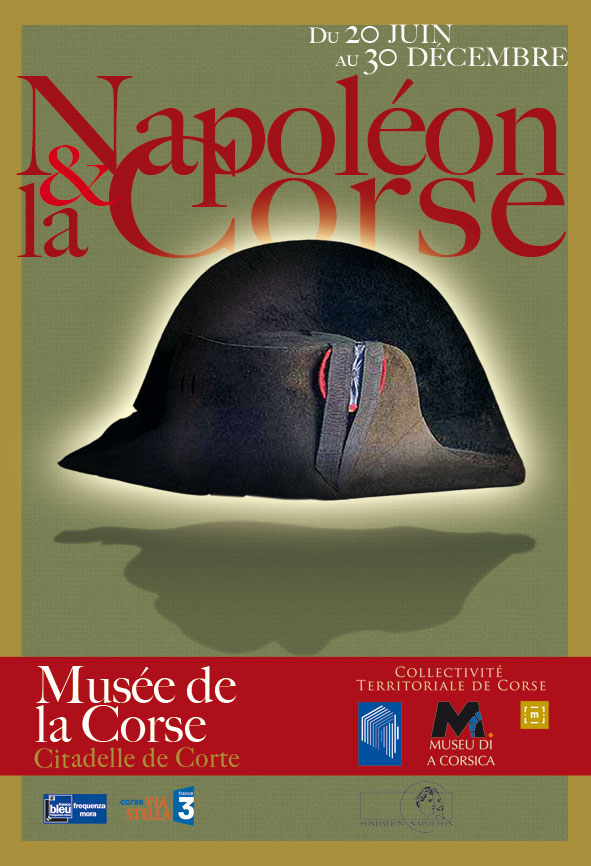

For the first time, an exhibition deals with the often ambiguous and changing relationship that Napoleon maintained throughout his life with his native Corsica and his fellow citizens.

The exhibition, and the important publication that accompanies it, endeavor to retrace for the first time the complex relationship that links Napoleon to Corsica and the role played by this insular and Latin origin in the destiny of the future emperor.

Who could have imagined the dazzling, but improbable, rise of a young Ajaccio man from an island that had just become French, so different in his culture, his origins, his codes and references, even his language, from the national political elites?

How did his Corsican identity serve as a springboard?

Was this extraordinary destiny accomplished despite the fact that he was Corsican or because he was Corsican?

How did a young scholarship holder of the King, nourished by the Paolian glory, solitary and taciturn, considered as an outsider by his comrades of the military school of Brienne, succeed in convincing himself of a possible “A nous deux le monde! ” ?

Did he choose the right party by becoming a Frenchman, at the risk of being considered a traitor?

Was Napoleon a son of the Revolution or of the Old Regime?

In Corte, the rooms of the museum will be organized into four major sections bringing together works and documents from Corsica, the continent and several European countries.

The Corsica of Bonaparte before 1795

traces the social ascension of this ambitious family. As the island passed from Genoese domination to that of France, the Bonapartes took a definitive position on the winning side. Divided between Corsicanness and Frenchness, the young Napoleon left Corsica for Brienne and then Paris where he learned to integrate into the society of his time.

1795 – 1815

Napoleon, first general of the Republic, then head of state at the age of thirty with the title of First Consul, proclaimed himself emperor in 1804. He remained marked, although he defended himself, by his Corsican identity and endowed his family with offices and titles, in the monarchic mode. At the same time, many Corsicans served in the administration and in the armies. His maternal uncle, the cardinal Fesch, constitutes an exceptional collection of paintings, in particular Italian, in order to offer it to his compatriots.

The ambiguity of Napoleon’s relations with Corsica

The reactions of the insular society relative to the dazzling trajectory of Napoleon are very varied: boundless admiration, indifferent lukewarmness or even systematic opposition, like that of Pozzo-di-Borgo. On the island, the emperor multiplied the urban projects favoring Ajaccio naturally, made roads and developed public works. On the other hand, he did not hesitate to repress the revolts of Fiumorbu by the troops of General Morand.

Stories, myths and memories

This last part develops the way in which history was rewritten, how Bonapartism developed and how Corsica appears in the testimonies of memorialists. Finally, the popular imagery around the Bonapartes from the 19th to the 21st century closes the exhibition.

This event also allows for a fundamental reflection on the very essence of French society: how to look at and analyze this France that is both universal and national, capable of incorporating “the other” by assimilating it, but often on the condition that it abandons its original identity?

General curator: Bernard Chevallier, honorary general curator of heritage, former director of the Musée National de la Malmaison, vice-president of the Fondation Napoléon.

Curator: Jean-Pierre Commun-Orsatti, scientific director of the Musée national de la Maison Bonaparte.

Scientific advisors: Luigi Mascili-Migliorini and Antoine-Marie Graziani.

Scenography: Michel Albertini.

CdC, musée de la Corse/Cl. P. Jambert

CdC, musée de la Corse/Cl. P. Jambert

CdC, musée de la Corse/Cl. P. Jambert

CdC, musée de la Corse/Cl. P. Jambert

CdC, musée de la Corse/Cl. P. Jambert

CdC, musée de la Corse/Cl. P. Jambert